It was midnight and Phil Kaufman was waiting. He’d been tipped off that the Manson crew had been crawling through his lawn at night when he was out of town. Sure enough when midnight struck he watched as several Manson followers did their infamous “creepy crawl” through his yard.

He waited patiently and when the first person stepped foot on his porch he yelled, “Stick ‘em up!” and they put their hands up.

“What the fuck are you doing?” Kaufman yelled out.

“Charlie sent us to get the music back,” one of the girls said.

Kaufman put a shotgun to the mans head and said, “Now you get the hell out of here and don’t you ever come back.”

After a tense standoff the group started to walk away but then he yelled, “Get out the way you came! Crawl out!” As they slithered away his buddy fired a shot at them. “You’ve never seen people wriggle along so fast,” Kaufman said.

Manson’s disciples came back still again. This time they surrounded the house and chanted, “Give us the music.”

IT WAS 1971 AND CHARLES Manson had recently been arrested along with four of his followers, all charged in the gruesome Tate-Labianca murders. It was the end of a several-year long drug-fueled experiment that saw a wannabe rock star morph into a dangerous cult leader.

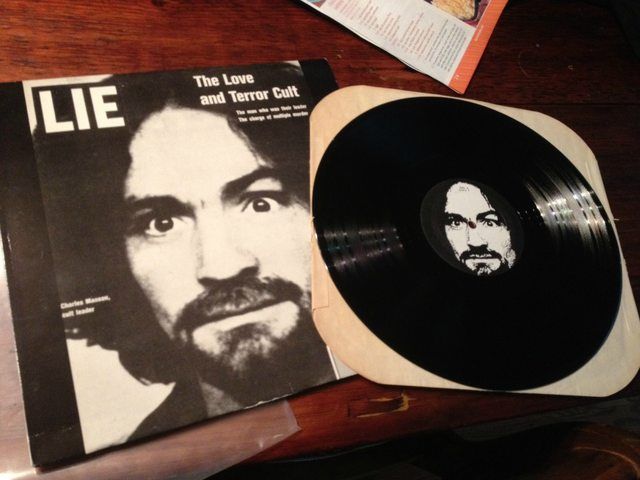

The music that the Manson followers came to get from Kaufman was 2,000 copies of his vinyl record titled Lie: The Love and Terror Cult. Manson recorded most of the album at Gold Star studios on August 8th, 1968, according to the record sleeve. Kaufman paid for the record pressing shortly after Manson’s arrest because he didn’t believe at first that he was guilty. His plan was to sell them to record shops but none would buy them. They wanted nothing to do with an alleged murderer.

Despite being in jail Manson still had followers who weren’t. These Family members needed food and selling the record was his best shot at feeding them. But Kaufman was determined to recoup the money he had invested.

The cover of the record Kaufman published had a photo from the LIFE magazine cover with Manson on it. The f was removed by another prison mate friend named Al Swerdloff and the title was Lie: The Love and Terror Cult.

“Nobody put their real name on the credits on the album,” Kaufman recalls. “Everybody put their prison number, or phony names like “Sunshine Al.” I’m “Phil 12258 CAL.”

“I own the rights to Charlie Manson’s recorded music,” Kaufman said. “My contract with Charlie was drawn up sometime before the murders. Ron Hughes, the lawyer murdered by the “family” at the time of Charlie’s trial, witnessed Charlie’s signature. I still have that piece of paper that says I own the Manson music—not an enviable possession.”

Despite his threats to the Manson family, Kaufman claims that they stole about half of the records.

Manson and Kaufman first met while he was in prison from 1961-1967. Kaufman saw Manson playing guitar one day and introduced himself, he recalls. Manson kept strumming along until the guard yelled, “You can’t play here! You have to play in that part of the yard.” Manson ignored him. “You’re never gonna get outta here,” the guard yelled. “Out of where man?” Manson replied.

While in prison Manson picked up Scientology, taking important attributes that’d he add to his tool bag. He also took a course in prison on the book How to Win Friends and Influence People. He learned how to manipulate people with the techniques.

Manson first learned to play guitar in prison where he also first heard the Beatles on the radio in 1964. From a young age he was a gifted musician according to family. He played piano as a child while living with his aunt and uncle. Manson was so talented that when he sang in church his grandmother believed the spirit of the lord would be descending down upon him.

After spending 7 years in jail, Manson was released just in time for the summer of 1967. He quickly descended on San Francisco where he lived briefly on 604 Cole Street for a few months. Janis Joplin, Jerry Garcia and other up and coming rock stars lived nearby. Manson soaked up the culture of the summer of love, got his first followers and soon headed to L.A. He landed at a place called the Spiral Staircase in Topanga Canyon, a sort of hippy commune.

Kaufman connected Manson with his producer friend Gary Stromberg in 1967 in L.A.. Impressed with his music, Stromberg set up a three-hour recording session with UNI records. The full audio of the session exists and Manson can be heard talking and giggling nervously. He sounded much younger than he was. It’s clear that Manson had never been in a studio before as his tracks sounded not much better than a busker on the street corner.

Manson set his girls out with a new task: find established rock stars on Sunset Strip and try to get his record signed. Almost immediately, two of followers were hitchhiking and were picked up by Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys in May 1968. He invited them over to hang out for a bit and they joined.

The girls were oblivious to Wilson’s star status, but when they told Manson later that day he demanded they take him back. When Wilson returned home late that night he walked into a dozen women partying topless in his house. When he saw Manson, he said, “Are you going to kill me?” Manson, replied, “Do I look like I’m going to?” He then kneeled down and kissed Wilsons feet as a gesture of good will. They hit it off. Wilson was always looking for something; he had thought he found it with Maharishi and now he had Manson and his spiritual message. Manson also supplied Wilson with a steady stream of drugs and women. Soon the Family moved into his house. And Manson hoped to tap into his deep connections in the industry.

Dennis Wilson got permission from his bandmates for Manson to record at the Beach Boys’ private studio. But the engineer said Manson struggled to sit still during the nighttime demo sessions. He eventually had to stop. “I can handle almost any artist's idiosyncrasies, of which Charlie had many, but it was the smell of this un-kept and un-washed human that I had to sit next to at the console that I could not or rather did not wish to endure any longer,” said the recording engineer Stephen Desper.

Despite Wilson’s attempts to turn on his Beach Boys bandmates to Manson they were not interested. Wilson had hoped to sign Manson to their label Brother Records but it never happened.

Manson did have potential but he he couldn’t take direction and his sound was too unpolished. “It’s the most complex of all of Manson’s songs in that period,” said author Simon Wells referring to Manson’s son “Look at Your Game Girl.” “It’s multi-layered. He harmonizes with his guitar. It has different tempos. His voice range is considerable. It’s a very well crafted piece of work.” The track was one of many that Manson used to speak to his followers, “Look at your game girl, come with me. “

Wilson also arranged for Manson to record at Sound City in 1969. The studio is legendary for having recorded Nirvana’s Nevermind, the Grateful Dead’s Terrapin Station, and Rumors by Fleetwood Mac among others.

"Sometime later [1969] I started recording Charlie at a little studio here called Wilder Studio,” said Greg Jakobsen during the Manson trial. Wilson had connected Manson with Jakobsen whom he was friends with. The owner was sketched out by Charlie and worried he may not get his money. “So Charlie turned to him and said, 'Aw, don't worry about your money. You can have all these guitars,” recalls Jakobsen. “And Wilder, dumbfounded, said, 'Wait a minute. What does he mean I can have all these guitars?' It really blew his mind. Charlie just walked out, saying, 'You can have 'em man.' He was bugged. He left him two or three amplifiers, two electric guitars, and acoustic guitar and some other instruments."

Manson couldn’t get a record deal with Kaufman, Jakobsen, Wilson or even Neil Young. So he set his sights on Terry Melcher, a young but prominent music producer for Columbia Records. As the son of famed actress Doris Day he commanded power and influence. His project at the time was the Byrds, which he turned into a sensational success.

Melcher was friends with Greg Jakobsen and Wilson and Manson slowly entered his world but was careful not to push his music on him. Eventually Melcher agreed to hear Manson play and traveled to the Spahn Ranch where he and the Family were living. Melcher also passed on signing Manson but he gave him the $50 he had in his pocket out of sympathy for the deplorable conditions they were living in.

Melcher lived at 10050 Cielo drive before Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski did. One theory of why Manson targeted the house for the murders is to send a message to Melcher for having failed to sign him and come through on alleged promises.

MANSON HAD A BAND CALLED Milky Way briefly while living at the Spiral Staircase in Topanga Canyon. He put out a call for young, gifted musicians and Earnest Knapp was the first to show up.

“So I went down there the next day and walked into Charlie’s living room,” Knapp recalls. “It was Charlie and his whole clan. He also had a couple of real gnarly kind of biker dudes with him who were not very nice at all. In fact, when and while I was setting up, one guy pulled a knife on somebody else and Charlie had to stop a big fight.”

Knapp nervously played a song by Cream to Manson’s liking and he was in. “We had one rehearsal and the rehearsal was really intimidating too,” Knapp said. “They brought in some other keyboard player from Malibu who I didn’t know and who was not very nice. The biker dudes started hassling me at the rehearsal. I remember Charlie stood up for me. I was twenty years old and the guys in the room were probably thirty back then.”

“We learned 8 songs and about half of them were Charlie’s and his songs, you know, were weird,” Knapp said. “They were kind of old fashioned jazz chords and real meandering progressions that didn’t go really anywhere.”

Knapp said they also learned a “few standards, rock and blues songs that everybody knew.” And a few days later they auditioned at the Topanga Corral, the same place where George Harrison heard Jiva play in 1975. But in 1968 it was a “full on redneck bar,” according to Knapp.

“So we went up and set up in the bar in the afternoon and played for the owner and some other kind of barfly guys hanging around,” Knapp said. “It didn’t go over at all with them. This was a country western bar.”

They were auditioning for a weekly spot at the venue and didn’t get it. Manson’s band was short-lived but he was determined to make it big as a musician. He wanted to use music to get his message out.

EVEN ROCKER NEIL YOUNG CAME into Manson’s orbit. They crossed paths a few times in 1968. Young met Manson through their mutual friend Dennis Wilson.

“We just hung out,” Young recalls. “He played some songs for me sitting in Will Rogers’s old house, on Sunset Boulevard.”

“I visited Dennis a couple of times and Charlie was always there,” Young recalls. “I think I met him three times. Spent the afternoon with him, Dennis, and all those girls—Linda Kasabian, Squeaky Fromme. They only paid attention to Charlie.” He thought their single-focused attention was odd given how famous Wilson and himself were.

“He was an angry man,” Young said. “But Brilliant. Wrong, but stone-brilliant. He sounds like Dylan when he talks.” He said Manson was “great, he was unreal… I mean, if he had a band like Dylan had on Subterranean Homesick Blues.”

Young even tried to help Manson get a record deal. “I told Mo Ostin of Warner Brothers about him. ‘This guy is unbelievable’ – he makes up the songs as he goes along, and they’re all good.”

Nothing came of Warner Brothers, but Young gifted Manson a motorcycle. In a later interview Manson said the people in the music industry “didn’t give me shit” except for Young.

“I remember playin’ a little guitar while he was makin’ up songs,” Young recalls. “Strong will, that guy. He’s like one of the main movers and shakers of time—when you look back at Jesus and all these people, Charlie was like that. But he was kind of… skewed. You can tell by reading his words. He’s real smart. He’s very deceptive, though. Tricky. Confuses you.”

In 1974 Young released the track “Revolution Blues” on his album On the Beach. The song was about Manson. He wrote it from the perspective of the group.

Well, we live in a trailer at the edge of town

You never see us 'cause we don't come around

We got twenty five rifles just to keep the population down

…

I got the revolution blues, I see bloody fountains

And ten million dune buggies comin' down the mountains

Well, I hear that Laurel Canyon is full of famous stars

But I hate them worse than lepers and I'll kill them in their cars

Like Neil Young, Phil Kaufman also tried to push Manson’s music to Warner Brothers to no avail. So Kaufman published the record on his own and tried to sell it, with no success.

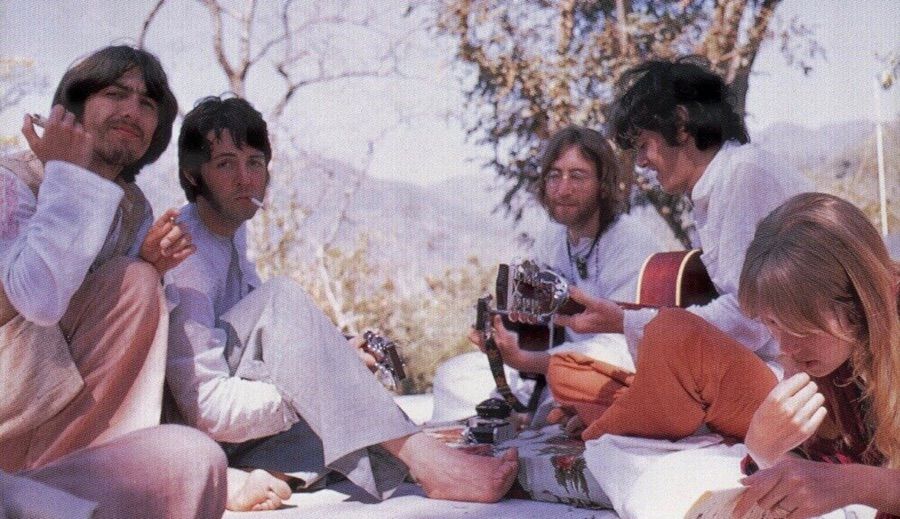

WHILE THE BEATLES WERE EXPANDING their minds in India they wrote many of the songs for The White Album. Manson heard it soon after it was released in November of 1968. His previous obsession with the group went to the next level when he started telling his followers the Beatles were communicating his own messages through The White Album. He claimed it supported his idea that a violent race war would soon unfold. “He said their album, The Magical Mystery Tour, expressed the essence of his own philosophy,” said ex-Manson follower Paul Watkins. Manson spent years brainwashing his members with these types of ideas, often while feeding them acid and engaging in orgies.

Manson listened to The White Album repeatedly and became transfixed. Former Family member Diane Lake said he played the album over and over again “because he wanted it to penetrate our consciousness.” She said Manson claimed the Beatles “know all about revelations and what is going to come down.” She heard Manson say more. “They have been sending me messages through their music. They have been looking for me. They know that Man’s Son is here on earth to carry out this mission, but they haven’t known who I am.”

The Beatles track “Helter Skelter,” “became the key, because it sounded like chaos and destruction,” said Lake. “From then on, the song title stood as our not--so-secret code name for the race war between the blacks and whites and the coming apocalypse.” Helter Skelter then became their euphemism to describe the race war i.e. that black people were going to “come down and rip the cities apart” said member Tex Watkins.

Helter Skelter was the name of a roller coaster in England. However, Manson interpreted it as a sign of the coming race war. “When you get to the bottom, you go to the top,” the lyrics say. Manson thought this referred to black people rising up from oppression to overthrow white people. Manson believed the song “Sexy Sadie” was about follower Susan Atkins aka “Sadie Mae Glutz.” The song “Revolution 9” referred to Revelation 9 in the Bible he thought. And it was more evidence for the upcoming revolutionary race war. The track “Piggies” referred to the established according to Manson and implied that they “needed a damn good whacking,” as the lyrics say. Manson would have his girls write out “Pigs” on the walls in the blood of those they murdered. “You were only waiting for your moment to arise,” the song Blackbird says. More evidence of the coming race war.

Manson was planning to hide out at a place called Barker Ranch which was hundreds of miles away, isolated in Death Valley. When the race war was over, he and his Family would rise up and take over. He told his followers that if they left him they’d be enslaved by black people. In the process they stocked up on dune buggies, guns, and knives.

Of course the race war never happened. Manson and several of his followers were sent to prison for life. While in prison the remaining family members on the outside recorded an LP called The Family Jams. Manson would later record several albums from prison. There have been several prominent covers of his music over the years including by Marilyn Manson, Guns n’ Roses, and the Lemonheads. Nine Inch Nails frontman Trent Reznor moved into the Tate murder house, making it a recording studio. His twisted legacy lives on through music, the same medium he used to spread his message.

-> READ PART 5: CARLOS SANTANA BECOMES DEVADIP