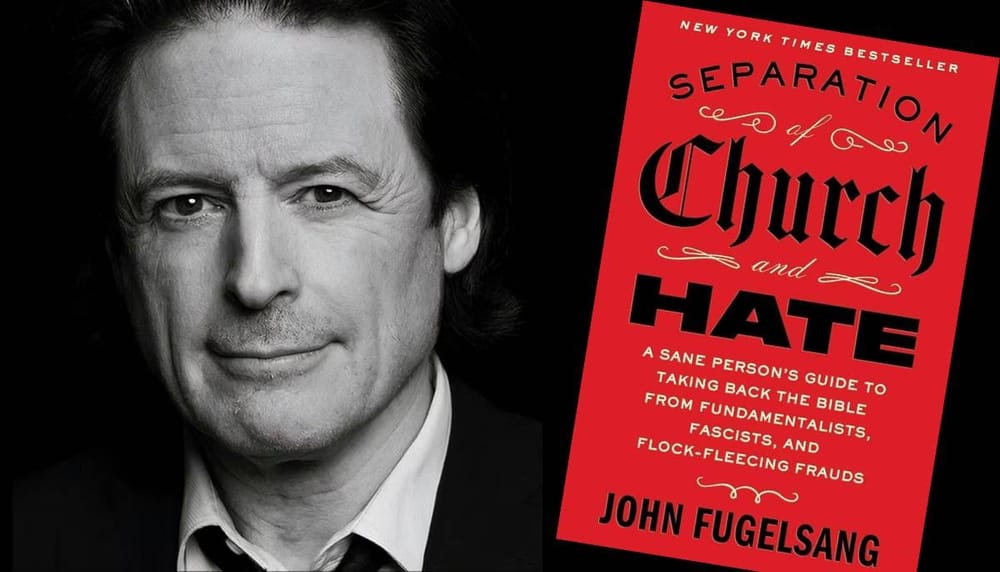

One strategy to combat far-right Christian nationalism is to try and make the “real” Jesus a liberal feminist. John Fugelsang attempts and fails tragically at this in his new book Separation of Church and Hate, where he gets nearly everything wrong about Jesus.

Be Scofield is a prominent cult reporter whose reporting is cited by the NY Times, Rolling Stone, People, and more. Her work has led to the hit HBO series Love Has Won, as well as Dateline, VICE, the Dr. Phil Show, and a Netflix episode. Scofield has a Master of Divinity from the Graduate Theological Union. She is a relative of C.I. Scofield, author of the Scofield Reference Bible.

12/25/2025

By BE SCOFIELD

“There is no historical task which so reveals a man’s true self as the writing of a Life of Jesus,” Albert Schweitzer wrote in The Quest of the Historical Jesus. The line has endured because it captures a recurring pattern in scholarship and popular writing alike: portraits of Jesus often become, in part, portraits of their authors.

In Separation of Church and Hate, John Fugelsang offers a contemporary version of that tendency. He presents Jesus as a critic of capital punishment, a champion of women’s equality, supportive of LGBTQ inclusion, skeptical of capitalism, and sympathetic to immigrants. He is a figure whose moral and political profile tracks nearly identically with the author’s own.

Fugelsang is a comedian with no experience in theology. Had his debut book not spent around eight weeks on the NY Times bestseller list, it could perhaps be ignored for the amateur tome that it is. But it's made such a splash that celebrities like Anne Lamott and Willie Nelson have praised the book for its “biblically correct” takedown of far-right political rhetoric. Fugelsang has also made high-profile appearances on The Daily Show and other leftist news networks that have uncritically accepted his claims.

Before we go further, let me break with the Fugelsang trend and admit that as a politically progressive queer-identified writer, Jesus does not reliably map onto my politics. Jesus was a deeply conservative man whose views would have reflected the surrounding culture. I have no qualms admitting that Jesus was most likely pro-life, against homosexuality, supportive of the death penalty, and rigidly patriarchal. It is for this reason I believe the left should not look to him for inspiration.

Fugelsang is searching for a liberal feminist inside what amounts to the Taliban. By any measure, Jesus’s culture was theocratic and draconian. Homosexuality was punishable by death, education for girls and women was shunned, they could be sold into sex slavery, blasphemy laws criminalized adherence to the wrong faith, abortion was outlawed and viewed negatively, and slavery was widespread.

The Gospels do show Jesus “on the record” about what he considers urgent moral danger in his society. Unfortunately, it’s all the wrong things. Jesus repeatedly targets the petty and trivial: lust, anger, name-calling, divorce and contempt. “Whoever says, ‘You fool!’ will be liable to the hell of fire,” he warns in the Sermon on the Mount.

Jesus never condemns or critiques slavery, patriarchy, anti-abortion laws, or the draconian rules against homosexuality and blasphemy. His silence has undoubtedly led to centuries of church oppression and discrimination that would have been rebuffed by clear statements from Jesus. When a “public moralist” makes a career of naming society’s sins, the omissions do not read as neutral. What goes unchallenged is seemingly accepted for someone who has "timeless" divine wisdom and is a supposed moral genius.

Homosexuality

Fugelsang dedicates an entire chapter to homosexuality in the Bible. While he rightly calls out Christians who cite passages against same-sex relations while ignoring the ones about shellfish and clothing, his effort is ultimately futile. His strategy is to try and downplay the infamous passages such as Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 that state homosexuality is an “abomination” punishable by death by claiming “many scholars” view them as about adultery or incest. This is false. Only a few fringe gay scholars have advocated such views. One of them, Theodore Jennings, wrote a book called The Man Jesus Loved: Homoerotic Narratives from the New Testament. Mainstream scholars and historians overwhelmingly accept that the passages in Leviticus refer to same-sex relations.

In a podcast appearance, Fugelsang said “A lot of scholars think Paul was gay”—another false claim. When you examine the receipts, the main scholar advocating this is once again the author of The Man Jesus Loved.

Jesus never condemns or critiques slavery, patriarchy, anti-abortion laws, or the draconian rules against homosexuality and blasphemy.

Fugelsang then claims the Levitical laws were a guide to help “keep your tribe’s numbers up.” But the Bible’s own story doesn’t present Israel as a tiny group scraping by. Numbers gives census totals so huge they imply a population in the millions. That is not “low”; rather, it’s hyper-abundant. And Leviticus reads less like a fertility plan than a holiness regime: rules that draw bright lines around sex, food, blood, bodies, and contact. It then hands the keys to a priestly class that gets to declare what is clean, what is dangerous, and who belongs. In that world, “survival” is real, but the central project is identity, separation, and authority.

Next he reaches for a kind of utopian shorthand to make his case: “What Jesus does is demand a radical love that transcends social boundaries and embraces all people, including those marginalized or rejected by society.” How? Jesus had an opportunity to show the LGBTQ community “radical love” by condemning the use of the death penalty for homosexuality, and he chose not to. Imagine the centuries of discrimination he could have prevented had he spoken up for the “cause.”

Fugelsang next piles on the familiar lines: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” “Do to others what you would have them do to you.” “Judge not.” In a culture where morality comes from scripture, we cannot assume that a teacher has rejected a rule simply because he also utters a general ethic of kindness. People of every political persuasion claim to obey the golden rule. We shouldn’t forget that Christians believed in these same ideals while enslaving and colonizing millions—they are no guarantee against troubling views or bad behavior.

Despite his best efforts, Fugelsang cannot rescue Jesus from the predominantly negative bias against homosexuality in Jesus's culture—views he would have also shared.

Abortion and the Death Penalty

“Jesus was a first-century Jew, and Judaism does not forbid abortion,” Fugelsang writes in Separation of Church and Hate. This grossly misrepresents the view in Jesus’ culture. First-century historian Josephus explains that Jewish law “forbids women to cause abortion” and says women who do are treated as a “murderer of her child.” Abortion was forbidden and morally condemned at the time. While there is no “thou shalt not abort” verse, they used multiple Biblical passages to frame their views.

“But Jesus never once gets around to condemning women who terminate pregnancies, or the individuals who help them,” he says in his book. He didn’t need to. It was already widely condemned, forbidden and heavily stigmatized in Jewish culture. He simply went along with the pro-life status quo. There was no urgent outbreak of abortions in his hometown.

Fugelsang also wrongly declares in interviews and in his book that in Numbers 5, “God gives detailed abortion instructions.” The passage never mentions pregnancy, a fetus, or terminating a pregnancy. It describes a jealousy ritual—a public ordeal for a woman accused of adultery, carried out by a priest, using “holy water” mixed with dust from the sanctuary floor. The threatened outcome is vague bodily harm and social ruin: her abdomen “swells,” her thigh “falls away,” and she becomes a curse among her people.

Fugelsang describes this as “an induced miscarriage, also known as abortion.” Scholars disagree. For centuries they’ve wondered what the passage means, but they don’t reach his conclusion. Only a small handful of feminist and pro-choice interpreters have tried to make this vague passage into a God-sanctioned abortion.

If Jesus was “so feminist!” as Fugelsang claims, he would have spoken up for women’s rights—especially if he had divine “timeless” wisdom that would transcend the cultural prejudices of his day. He protests in a podcast, "For 45 years they persecuted women by trying to criminalize abortions!" Jesus's silence on the issue greatly contributed to this persecution. Just imagine how differently the Supreme Court deliberations that led to the overturning of Roe vs. Wade could have gone had there been a clear message from Jesus.

Fugelsang also emphatically states that Jesus was “completely anti-death penalty.” The main passage he cites in his book and in interviews is John 8, the infamous story of Jesus telling the crowd about to stone the adulterous woman, “Let any one of you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” He claims the passage is “Jesus’s most direct rejection of executions in the Bible.”

There is a huge problem for Fugelsang: mainstream scholars and historians widely agree this story is not original to the Bible. It was added later. The “moment” Fugelsang claims is “essential to Jesus’s entire ministry” is a creative addition put in his mouth.

Even if John 8 were authentic, it doesn’t mean what Fugelsang thinks. The passage states they were trying to “test him." It was a setup, an effort to trap Jesus in one of two ways: either by rejecting stoning and appearing to be against Moses or by siding with stoning and risking endorsing a potentially politically dangerous execution under Roman rule. The Pharisees were searching for something to accuse him of to undermine him or report him for inciting mob justice. The passage illustrates him escaping a trap, not rejecting the death penalty. A clever evasion under pressure is not the same thing as a moral doctrine against capital punishment.

Imagine how differently the Supreme Court deliberations that led to the overturning of Roe vs. Wade could have gone had there been a clear message from Jesus.

“Jesus wastes no time overturning all death penalty laws at the very beginning of his public ministry,” Fugelsang writes. He claims Jesus overturned “eye for an eye” in the Sermon on the Mount. He then once again resorts to a generic ethical statement Jesus has said, “Do to others what you would have them do to you.” He claims this “compassionate reciprocity is to be extended to all, including the worst of us.”

Fugelsang misreads what Jesus is doing here with "eye for an eye." He confuses instruction for his disciples with legislative reform of Judean law. Jesus is teaching his followers how to absorb humiliation and persecution without retaliating—rules that keep the group cohesive and limit blowback when hotheaded followers pick fights with outsiders. In simple terms, it's crowd control for a movement under pressure. He was not trying to repeal the penal code. Just look at who he's speaking to. It's not government officials in town. Furthermore, Jesus explicitly declares in the same sentence that he did not come to abolish the Law or the Prophets, including the harsh punishments that Fugelsang asserts were being dismantled.

If Jesus were “completely anti–death penalty,” it’s odd how often he reaches for execution and torture as morally appropriate punishment in his teaching stories—and never pauses to condemn it. Jesus frequently uses the very real terror of state-sanctioned execution to illustrate the severity of God’s judgment. Slavery is so normalized in Jesus’s day that he repeatedly uses it as casual teaching examples to make a point.

Fugelsang has to ignore a whole trail of passages that point in the other direction: Jesus cites “whoever curses father or mother must be put to death” (Mark 7:10/Matthew 15:4); he describes a master who “cuts [a slave] to pieces” (Matthew 24); he ends a kingly parable with enemies “slaughtered” before the throne (Luke 19:27); and he repeatedly frames divine judgment as burning cities, violent ends, torture by “jailers,” and angels throwing people into a furnace (Matthew 21–22; 18; 13).

In Luke 17, Jesus asks his disciples, "Who among you would say to your slave... 'Come along now and sit down to eat'?" Jesus answers no one. You tell the slave to make your dinner first, he says. You don't thank the slave for doing his job. Jesus says his followers should be like the unworthy slave, "So you also, when you have done everything you were told to do, should say, 'We are unworthy slaves; we have only done our duty.'"

It's hard to imagine someone against the death penalty using examples of misbehaving slaves being cut up and killed in normative teaching stories. If anything, this illustrates that Jesus was a product of his era—unable to condemn slavery and unaware of how offensive and cruel it was to use it in his stories. This is yet another reason the left shouldn't turn to him for insights.

Social Justice

Fugelsang loves Matthew 25. He repeats it dramatically in interviews and anchors his entire political thesis on the "Judgment of the Nations," calling it "Jesus’s memo to the Heritage Foundation." In his view, this passage shows Jesus delivering a broad mandate for modern social welfare. Fugelsang treats it as proof that Jesus wrote a progressive political platform, but he misreads the context of the speech.

The scene depicts the end of the world, where the Son of Man sits on a glorious throne and separates the "nations"—specifically the Gentiles—like a shepherd separating sheep from goats. The key line here is “the least of these brothers and sisters of mine.” In the Gospel of Matthew, “brothers” isn’t a generic word for humanity, and "the least of these" isn't a shorthand for the global poor. These are Jesus’s insider terms for his own people—the disciples who left everything to spread his message. And this is whom he is addressing. Elsewhere in Matthew, Jesus uses these phrases, "brothers" and "least of these," specifically to refer to his disciples.

When Jesus says, "For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me," he is not describing a universal social ethic for the world to follow as Fugelsang imagines. Rather, he is describing how his specific messengers look on the road—vulnerable, dependent, and often jailed for their mission. He often required them to travel with no food or money. The judgment is based on whether the "nations," i.e., the Gentile world or outsiders, showed care to Jesus's followers or treated them like trash.

Fugelsang distorts this in-group promise of vindication into a general mandate for social justice. But Matthew 25 is a scene of judicial power. Jesus isn't acting as a social reformer here. Rather, he is a divine king sitting on a throne, issuing a threat and a promise. He is telling his inner circle, in private, that their hospitality is the line between "eternal life" and "eternal fire." Far from a message of "radical inclusion," it is a final, violent separation of the in-group from the out-group.

Those who mistreated them "will go away into eternal punishment," but the "righteous ones will go into eternal life.” This is also another sign that Jesus wasn't a social reformer. Rather, he presents himself as a divine king who will judge everyone. Whereas Fugelsang misreads his efforts as a call for social welfare, it's actually a threat and a promise to his followers that they will be protected.

We should address one of the most famous passages attributed to the "anti-capitalist" Jesus: the flipping of the money exchange tables in the temple. This was not an assault on "capitalism," however. It was an assault on rival sovereignty. Jesus had sold his followers on positions in what amounted to an alternative government—they would be judges ruling over Israel. By trying to shut down the access-and-revenue pipeline in public, Jesus acts like the higher judge who can declare the whole system corrupt and obsolete. It’s a monopoly move: provoke a crisis, force polarization, and re-route loyalty from the old regime to himself as the center of the coming kingdom.

Jesus’s coming kingdom was no communist society based on equality. Hierarchy was still in place; it was just flipped upside down. “Woe to you who are well fed now, for you will go hungry,” Jesus said, meaning outsiders will be excluded from the feasts. The poor will be "blessed," and the rich will be "shunned." The first will be last, and the last will be first. This is no egalitarian vision. This was a delusional prophetic role reversal. Jesus promised his followers power at the top: “At the renewal of all things, when the Son of Man sits on his glorious throne, you who have followed me will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel.”

Care for the Poor

The misreading of Matthew 25 is the perfect segue to Fugelsang's chapter on the poor. "Jesus gave welfare to the poor constantly—free food and healthcare—and never asked for a co-pay," he writes. This interpretation is comforting but not supported by the data and evidence.

Let's start with the easiest claim to test: food. The Gospels contain only two accounts of Jesus feeding people. Both are miraculous events where he transforms a few loaves of bread and some fish into enough food for thousands. Historians can't certify these as real—at most they may think a similar event happened and he tore off tiny bites for the crowd that served as a communal ritual to induce members into the group. Outside of these mythical stories, there are zero accounts of Jesus or his disciples providing food to the poor.

Jesus could have organized low-profile and decentralized systems of relief. He and his followers could have had a few people regularly bring bread and grain to known households of widows, the sick, day laborers, single mothers or the disabled. The group could have left food on credit with a vendor or prepaid bakers or grain sellers and given tokens to the needy to pick it up.

The Gospels never actually show Jesus or his disciples handing money to a poor person. John only implies that giving alms was a plausible use of the group’s funds. Such generosity was a basic religious obligation, however, almost like a tax. It was a culturally expected piety, and would have happened only intermittently. The group is never shown providing ongoing financial support for the poor.

Fugelsang claims that Jesus provided free "healthcare" to the poor. Yes, he supposedly healed people through "miraculous" means, but that does not constitute a health clinic. Furthermore, historians cannot certify the reality of mythical claims of healing: "The whole town gathered at the door, and Jesus healed many who had various diseases." Imagine if Jesus had left a network of organizations that provided long-term health support to the poor.

Crucially, most of the people Jesus healed were not poor. The majority would have been ordinary citizens of Judea with homes, families, and trades. Of the few dozen accounts described in the Gospels four were high-status or explicitly wealthy, three were middle class, and 15 were undesignated. Of those undesignated, these happened in towns or the Temple; they were most likely regular citizens. There are only four accounts of him healing people described as destitute beggars.

The common denominator in all the healing stories is submission to Jesus, basically being willing to fall at his feet and pledge loyalty. He used healing to hook them for his end goal of submission. Like many other teachers of his time, Jesus used claims of miracles to boost his status and recruit followers.

Let's take the story of the Syrophoenician woman, who is a non-Jew, in Matthew 15. When a desperate mother begs for her daughter’s life, Jesus initially meets her with silence. When his disciples ask him to send her away, he articulates a rigid, nationalist mission statement: “I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel.” When the woman persists, kneeling before him, Jesus offers an insult that underscores the theocratic order of his world: “It is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs.” Here he is stating a hierarchy. In this worldview, Jews are the children; Gentiles are the scavengers. He refers to her as a dog.

The healing only occurs once the woman accepts the slur and acknowledges her place at the bottom of his order. “Yes, it is, Lord,” she replies. "Even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table.” Only after this total psychological submission does Jesus grant the request: “Woman, you have great faith! Your request is granted.” The daughter’s health served as the bargaining chip used to extract a confession of ethnic and spiritual inferiority.

In another story, Jesus heals ten lepers, and after only one returned to fall at his feet, he became visibly offended. "Were not all ten cleansed?" he protested. "Where are the other nine? Has no one returned to give praise to God except this foreigner?” He then dismissed the one who did return by telling him, “Your faith has made you well,” implying that the physical healing was secondary to the act of submission. For Jesus, the nine who didn't worship him meant that the visit was a failed recruitment mission.

"He never healed the blind and billed them," Fugelsang writes. Jesus wanted a different form of payment: worship, praise, loyalty, free labor and submission.

If anything, Jesus stripped assets from his followers—they were required to give up their wealth, families, jobs, and lives to totally submit to him. Joining his group was a high-risk downgrade. Wealth equals autonomy in Jesus’s world, and it prevented people from following him. When you give up your home and money, you lose your independence and become totally dependent on the leader for survival.

The famous story of the rich man illustrates this, as Jesus told him to sell his things and follow him. Immediately after the man refused to join Jesus's "kingdom of God" movement, Jesus protested, “How hard it is for the rich to enter the Kingdom of God!...In fact, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the Kingdom of God!” Jesus complained that he lost a potential new recruit because they were rich. It wasn't an economic protest against the wealthy—once again, money and resources were barriers for people to become new followers. Fugelsang misreads this as an action that is aligned with "socialist principles."

In Jesus’ mindset there was no need to organize long-term for the poor. He had told everyone to quit their jobs, sell their things, leave their families and follow him because the world as they knew it was ending. The new kingdom of God on earth was imminent—the poor would be blessed and the rich shunned. It was an apocalyptic power shift, a role reversal of epic proportion.

He had sold them on his prophetic role reversal fantasy: the last would be first, the poor would be blessed, and they'd rule his kingdom as judges. He told them they "will receive now in return a hundred times" of property, family...etc., those things they gave up. They would be ruling in a heavenly kingdom. This is a standard cult "heaven on earth" utopian fantasy that sells their followers on the same vision. None of Jesus's promises came true. Ranting about the rich and poor is not the same as materially supporting the downtrodden—many politicians or populists use such rhetoric to rile people up, but their actions don't match. His perhaps deluded quest to become the messiah ultimately left hundreds of his followers worse off.

There is one more passage we need to address on this topic. It’s often portrayed as a call for selfless love that prioritizes “radical generosity” and “people over possessions.” It is Matthew 5:42: “Give to the one who begs from you, and do not refuse the one who would borrow from you.” Put in context, it looks different than the surface reading.

Similar to Jesus telling his followers to turn the other cheek and love their enemies, this passage is an instruction to his people to keep them safe and out of trouble, not a global ethic of justice. The verses right before it describe how a Roman soldier can force you to carry his gear or how a wealthy man can drag you into court and strip you of your clothes. In that world, you do not win by resisting. You win by not becoming a target.

His perhaps deluded quest to become the messiah ultimately left hundreds of his followers worse off.

If a soldier can legally conscript you for one mile, going two is a way of avoiding trouble with someone who has a sword and the state behind him. If a creditor sues for your tunic, surrendering your cloak as well cuts the conflict short before it turns into something worse. In that context, “give to the one who begs” and “do not refuse the one who wants to borrow” become practical advice: do not start fights over money and property with people who can ruin you. Hand it over and live to see another day.

Under empire, that kind of strategy is understandable. It also produces a very compliant style of disciple. A follower who does not resist, does not push back, and is trained to release possessions on command is easier to move, easier to exhaust, and easier to keep dependent. For a leader running a costly, full-time road campaign funded by other people’s resources, a community conditioned to yield rather than challenge is highly efficient.

The Guru MagazineBe Scofield

The Guru MagazineBe Scofield

Women and Feminism

“If God loves men and women equally, then God’s a feminist,” Fugelsang announces at the top of his chapter on women. A few pages later he admits the obvious: women have it rough throughout the Bible. They’re cursed. They’re treated as unclean after childbirth (and “extra unclean” if the baby is female). They’re barred, controlled, traded, and punished under rules written by men and enforced by priests. Fugelsang even jokes that it reads like “the Gospel According to Ike Turner.”

Based on Fugelsang's own words, it appears that God doesn't treat men and women equally. But then we realize that he waffles between the "God of the Bible" and a utopian "God" of his liking that is apparently feminist. If Fugelsang were intellectually honest, he'd acknowledge it was God who gave Moses the draconian law in the Old Testament that dictates the rigidly patriarchal, oppressive, and cruel treatment of women. This is the Christian God that is supposedly the subject of his book.

After listing the terrible conditions women faced during that time, he declares Jesus to be “the biggest damn feminist in the entire Bible,” suggesting that the Gospels serve as a corrective to the previous patriarchy. He claims the Old Testament is a rigged game, and Jesus shows up and “almost ruins it.” There is a major flaw here, however. Jesus is the same God who “rigged the game,” according to tradition. The Old Testament's sexist divine commands were written by Jesus, who is God.

It’s not “feminist” to be included in a high-demand group so you can worship a self-proclaimed messiah.

Fugelsang next goes through several stories of Jesus breaking taboos by engaging with women. What he reads as “feminist” are actually stunts to showcase his charisma, authority, and mythical powers. He uses women as props in his teaching, recruits them, and depicts them groveling at his feet.

We should also note that many cults include women. Jim Jones famously included the most marginalized of his day—poor Black women. He also had four white women in leadership positions; they actually planned the final murder/suicide. Keith Raniere of NXIVM also recruited women throughout the senior leadership ranks. It’s not “feminist” to be included in a high-demand group so you can worship a self-proclaimed messiah. Cult experts are wary of charismatic men who include women to fund their efforts, recruit new followers, and pledge loyalty to them as Jesus did. For what purpose do these women need to serve him? Why does Jesus's movement even need to exist?

Fugelsang misreads several of Jesus's encounters with women as "feminism," but they serve his broader agenda. They were the major funders of his movement—stemming from well-off backgrounds. Had Jesus stripped everyone of their assets, the ability to travel the desert with an entourage of 20-30 people would have been short-lived. So he targeted women who had financial means in a culture that undervalued them, gave them little power, and often left them desperate for recognition. The same tactic worked for the low-status tax collectors and sinners. These people were craving recognition. Jesus offered them a role in what he said was a special, divinely chosen religious movement. It was the ultimate opium of the people.

The Sinful Woman in Luke 7

The scene in Luke 7, where a "sinful woman" wets Jesus’s feet with her tears and wipes them with her hair, is frequently cited as a moment of tender compassion. In actuality, it's a display of power. As Jesus dines with Simon the Pharisee, he allows the woman to perform an act of extreme, public devotion. He could have stopped her and empowered her. He could have offered her a seat at the table. Instead, he lets her wipe his feet so he can use her as a moral weapon to humiliate his host.

Jesus turns to Simon and pointedly asks, “Do you see this woman?” He then proceeds to list Simon’s failures in hospitality compared to the woman’s grovelling worship. She is the "state prop" in a status contest between two men. Jesus wins the argument, the Pharisee is shamed, and the woman is sent away with the spiritual currency of "forgiveness." Her life hasn't materially changed. She is still an outcast, but Jesus has used her to demonstrate his superior rank.

Martha, Mary, and the Samaritan

In the domestic dispute between Martha and Mary in Luke 10, Jesus’s defense of Mary’s "better portion" is often read as an endorsement of women’s education. However, it looks much more like a recruitment strategy. By telling Martha that Mary’s place is at his feet rather than in the kitchen, Jesus is asserting that loyalty to him supersedes the domestic duties that held ancient families together. He isn't liberating Mary from "gender roles"; rather, he is liberating her from her family obligations so she can serve his mission.

The same logic applies to the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4. Jesus uses his supernatural knowledge of her five husbands to stun her into submission. He doesn't offer her a way out of her social predicament or address the systemic reasons for her domestic instability. Instead, he reveals his identity as the Messiah, turns her into a local recruiter, and leaves. In these "feminist" moments, the woman’s personal trauma is merely the "shock and awe" required to secure her total commitment to his cause.

The Bleeding Woman

The healing of the woman with the issue of blood in Mark 5 demonstrates "rank." She touches his cloak and is healed, but Jesus refuses to let her slip away unnoticed. He stops the entire crowd and demands to know, “Who touched my clothes?” He compels her to step forward, "trembling with fear," and fall before him to reveal the complete truth.

This is a public validation of his mythic power. He requires her to go through the public ritual of submission before he grants her the final "loyalty" validation: “Daughter, your faith has healed you; go in peace.” Like the lepers and the blind, her body was the canvas, but the portrait being painted was of a king who demanded to be recognized.

These are only some of the examples. Every "feminist" scene of Jesus with women serves his agenda by growing his following, reinforcing his unique status, or centralizing moral authority in him. These stories do nothing to challenge or dismantle the broader patriarchal structure. His posture towards women was both as a recruitment strategy and as donor cultivation. For those who did make it in, he extracted their labor and money: hosting, caregiving and emotional intensity. Jesus was not running a women's rights campaign; this is cult dynamics 101.

Cults often operate like labor camps in the sense that a messianic leader turns belief into unpaid work for a “world-saving” mission. The Gospels show Jesus building a movement that runs on free labor—disciples who abandon jobs and family roles, locals who host and feed the operation, and patrons who bankroll it—framed as urgent kingdom work. The heaven-on-earth promise functions like every high-control pitch: your sacrifice is not exploitation; it’s proof you’re chosen for a "special" mission. For what purpose did this group need to exist? It had as much validity as David Koresh's messianic group.

Fugelsang also misreads Jesus's stance on lust. He quotes him from Matthew 5:28 "You have heard that it was said, 'You should not commit adultery.' But I tell you that anyone that looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart." He claims that this could be the first biblical "utterance" of "Eyes up here, buddy." He says it is "anti-sexual harassment." This, however, is evidence of Jesus's escalating purity code—further ways for him to enlist control over his followers' thoughts and emotions. Initially, Jesus's control focused on behavior, but he expands it to include policing their thoughts.

Cults often operate like labor camps in the sense that a messianic leader turns belief into unpaid work for a “world-saving” mission.

One of the few cultural issues Jesus voices opposition to is divorce. Fugelsang frames this as a pro-feminist move because he restrains men from discarding their wives. That is a silver lining; however, the rule is still harsh. It traps women. It makes remarriage a moral crime in many instances. It gives religious men a righteous excuse to keep women bound to bad marriages—a recurring problem in contemporary churches. Jesus's restrictions on divorce are yet another example of purity policy, a way for him to further control his followers.

Fugelsang suggests Jesus's women followers were not included as the twelve apostles because of manipulation by the church. "But women aren’t counted as people in the Bible, so any female apostles were officially decreed by the early church to have been sacred-adjacent groupies," he writes. This is an attempt to protect Jesus from his first-century patriarchal mindset. The evidence doesn't support this claim. Had the Biblical writers wanted to keep women out, they would have totally removed those whom Jesus allowed in.

In summary, Jesus's record on women's rights is poor. He could have addressed marital rape, domestic violence, forced marriage, sexual slavery, or other crises worthy of protesting. He doesn't challenge the property structure that treats women as assets, nor does he campaign for structural change. Instead, women are tokens in his charisma show—often used to prove his status, superiority or power. We see them repeatedly groveling at his feet. Once again, including women in his inner circle, extracting their wealth, and making them recruiters and loyal subjects is not a "feminist" move. These are brilliant power plays so he can wander the desert and play messiah.

Immigration

Fugelsang dedicates an entire chapter to immigration. From the start, we can see that Jesus is clearly an ethnic nationalist focused on his own people, the "lost sheep of Israel." He called his Jewish followers the "salt of the earth" and the "light of the world"—privileged titles reserved for the Jewish tribe. When Jesus sends his disciples out in the book of Matthew, he imposes strict restrictions: they are instructed not to go to Gentiles or Samaritans but to focus solely on the house of Israel. When a foreign woman begs for help, Jesus compares her people to "dogs" before ultimately relenting.

The "universalism" that people associate with Christianity—the "neither Jew nor Greek" ethos—is actually a later development, largely pioneered by the Apostle Paul long after Jesus was gone. The historical Jesus, as depicted in the Gospels, was a sectarian leader who viewed the world through a strictly ethnocentric lens. He was a king who came for his own subjects, and everyone else was just standing in the way of the throne.

"The God of the Bible consistently takes an unambiguously compassionate stance toward immigrants and strangers," Fugelsang writes. To pull off this claim he resorts to heavy cherry-picking of passages to make his case. As usual, he takes many examples out of context and extrapolates a singular geopolitical rallying cause of God.

The God of the Bible is many things, and there is a lot of ethnic favoritism. The Bible serves as a national origin story, and its narratives are often harsh. God chooses a particular people, gives them a particular land, and repeatedly frames surrounding nations as threats to be beaten, cursed, dispossessed, or punished. The Psalms celebrate the breaking of enemies. Prophets gloat over foreign cities falling. There’s a steady pace of “us” and “them,” and God is not neutral.

The slavery laws given by God illustrate just how rigid the treatment was between insiders and outsiders. An Israelite in debt servitude often goes free after six years. A foreigner can be owned as permanent property—kept “for your children after you,” inherited like land. Jews and foreigners do not have the same human value. God sets a clear ethnic boundary around his "chosen" people.

Israel’s entire identity is built on separation. The idea of “don’t intermarry” is commonplace. The fear is always the same: outsiders dilute the bloodline and infect the worship system. Deuteronomy warns Israel not to intermarry with the peoples of the land, “for they will turn your children away from following the Lord.” Ezra and Nehemiah go further and stage a public purge of “foreign wives.” This doesn't sound like Fugelsang's "unambiguous" compassion towards strangers. This is “We are a distinct people, and we intend to stay that way.”

God also “gives” territory to Israel, and that gift comes with a violent eviction notice for whoever is already living there. Deuteronomy says Israel is entering a land of other peoples, who must be "driven out." Sometimes the language turns into full-on annihilation rhetoric—whole cities “devoted to destruction.” The land is dedicated to "God's people," and the others are obstacles.

In his effort to paint the God of the Bible as pro-immigrant, Fugelsang misreads several passages of scripture. He treats Deuteronomy’s asylum protections for escaped slaves as a broad open-border policy and mistakes the aspirational prophecy of Ezekiel for historical law. Furthermore, he projects modern liberalism onto the command to "love the foreigner," failing to see that it calls for compassion within a distinct "chosen people" framework, not the erasure of national boundaries.

Conclusion: Jesus the Apocalyptic Guru

In Matthew 16 Jesus asks Peter, aka Simon, "But who do you say I am?" He responds, "You are the Christ, the Son of the living God." Jesus's reaction is immediate and telling. Instead of showing humility, he rewards the praise with power. "Blessed are you!...I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven."

The scene reveals a stark psychological contract: if you validate the leader's divinity, you will be granted authority; fail to do so, and you remain nothing. He had already promised his core apostles power for giving up everything to serve him. They will serve as 12 judges that will rule over Israel. Now, Peter's act of ego stroking got him the "keys of the kingdom of heaven." This is why Peter is considered the first "pope." This granting of power by Jesus is reminiscent of Trump, who gratuitously gives power away, often not on qualification but rather on who flatters him the best.

Fugelsang misunderstands who Jesus was and his purpose. He was not a liberal feminist trying to empower women or change society. He was a David Koresh-type character. Jesus ran a commune in the desert and sought people following him and groveling at his feet. He was an apocalyptic self-proclaimed messiah who claimed the world as he knew it was ending. Those who submitted would be rewarded in a "heaven on earth" utopia—a common thing for high-demand groups.

Jesus frequently utilized fear and terror to scare followers into submission—those who were not "in" would be violently discarded. He painted graphic pictures of the fate awaiting outsiders: being "thrown into the blazing furnace," "cut to pieces," or cast where "the worm does not die." He promised "outer darkness" and "eternal fire" for anyone who failed to recognize his divinity or meet his demands. By constantly referencing the "narrow door" and the vast majority who would be destroyed, he fostered a siege mentality where the only safety from God's wrath was total submission to God's Son. It was essentially spiritual extortion: Love me, or burn.

He wasn't creating structures to provide food, healthcare or money for the poor. Jesus was following a playbook, a standard blueprint of an apocalyptic disruptor. He declared the current world unsalvageable, manufactured a state of emergency, and then positioned absolute loyalty to himself as the only currency worth holding when the system collapses.

As he traveled with his disciples, he followed a rigorous, repeatable cycle: first, disciples were deployed as an advance team to scout towns, generate local buzz, and identify the sick for high-impact displays. Once the stage was set, the public spectacle commenced with a potent mix of charismatic sermons and healings, followed immediately by private indoctrination sessions to cement the disciples' loyalty. To sustain momentum, he then deliberately provoked local authorities, using calculated conflict to escalate the stakes and force the public to choose a side. It was an exhausting, high-stress, nomadic existence designed to break the groups' ties to the normal world and bond them trauma-style to their leader.

Everything Jesus said and did needs to be seen through his cult of personality and apocalyptic view. The sermons he gave, the lessons he taught, the flipping of the money tables, and the miracles he performed were all to a specific group of people. He wanted followers. And his low-status disciples found meaning, purpose, and security in his authoritarian hierarchical group—that is often the major selling point. Jesus was not giving lectures to the rulers about policy reforms. He was giving in-group statements to his own messengers about how they should live, treat people, and avoid conflict.

To make Jesus a liberal feminist, Fugelsang must extract his teachings from this insular context and misrepresent them as attempts at general societal reform. Jesus never intended his teachings for that purpose. He must also selectively choose passages from the Bible, highlighting those he agrees with and concealing the rest.

Crucially, Jesus was a first-century Jew who lived in a religiously conservative culture—one that was draconian and theocratic in nature. Since Jesus didn't offer us any statements to the contrary, it's highly likely he broadly agreed with the views of surrounding society. The culture was against homosexuality, pro-life, accepting of slavery, ethnocentric, patriarchal, and in favor of the death penalty.

In the conclusion of Separation of Church and State, Fugelsang pulls a rhetorical trick to name the Christians he agrees with as "Christ" followers. "When Confederate Christians justified human enslavement, Christ followers like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and the Quakers called out slavery as a moral abomination and resisted," he writes. It is yet another artificial concoction he invents to paint the "authentic" Christianity as his.

Fugelsang's heroes were on the losing side of the "Does the Bible support slavery?" argument, as it clearly does. Furthermore, Jesus never condemned slavery and often used brutal examples of it in his storytelling without critique. Paul also assumed slavery was normal and never condemned it. Rather, he gave instructions to slaves on several occasions like, “Slaves, obey your earthly masters in everything…Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord.” It took over 1,500 years for a few Christians to start waking up from the acceptability of slavery—and it wasn't because they were "Christ" followers. Rather, it was the burgeoning ideas of the Renaissance and Enlightenment eras.

It's a bad strategy for the left to try and combat far-right Christian nationalism by turning Jesus into a leftist social justice warrior. Fugelsang's effort is anachronistic at best and a massive deception at worst. To pull it off, he had to bury facts, hide history, grossly deceive the reader, pull stories out of context, and distort passages. His premise of Jesus as a liberal feminist in a first-century theocratic culture is so far-fetched that the publisher should consider pulling the book. If the Jesus you proclaim to speak for sounds exactly like you, as does Fugelsang's, you're probably mapping your views onto him.

If you want more cult analyses of Jesus and the Bible, please sign up below.

Sign up for The Guru Magazine

Investigating Cults & Gurus

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.